On this episode of There Has to Be a Better Way?, co-hosts Zach Coseglia and Hui Chen are joined by actor and activist Julia Ormond, founder and president of Asset Campaign, a nonprofit organization working to ensure human rights by driving supply chain transparency and empowering individuals to make informed purchasing, investment and employment decisions. Julia discusses the “aha” moment that inspired her work on human trafficking and outlines a broad strategy for how policies and businesses can begin to support global human rights efforts. She specifically points to measurement and transparency as powerful tools that can be used to change behavior and eradicate trafficking, slavery and forced labor.

Transcript:

Zach Coseglia: Welcome back to the Better Way? podcast, brought to you by R&G Insights Lab. This is a curiosity podcast, for those who ask, “There has to be a better way, right?” There just has to be. I’m Zach Coseglia, the co-founder of R&G Insights Lab, and I’m joined, as always, by my friend and collaborator, Hui Chen. Hi, Hui.

Hui Chen: Hi, Zach. Hello, everyone.

Zach Coseglia: We have a very exciting podcast today. Hui, I’m going to let you tell us a little bit more about our guest.

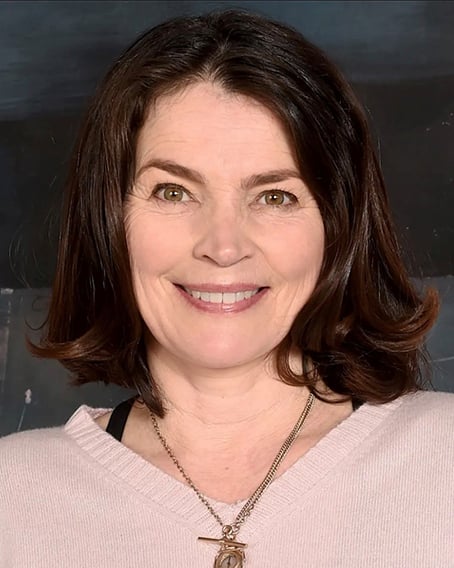

Hui Chen: Our guest requires very little introduction. We have the one and only Julia Ormond with us today. She’s here to talk about her passion about fighting against human trafficking. Julia, welcome—thank you so much for being with us today.

Julia Ormond: Thank you, Hui. Thank you, Zach.

Zach Coseglia: We’re really excited. I always ask an existential question to our guests, which I will ask you. But also, because you are one of the few guests who most of our listeners may know, I do also want to give you a proper introduction. You will know Julia from films like Legends of the Fall, First Knight, Sabrina, and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. You may also be familiar with her Emmy-nominated guest appearance on Mad Men as Don Draper’s mother-in-law, or her Emmy-winning turn in HBO’s Temple Grandin. You might also know her as one of the stars of Walking Dead: World Beyond, and so much more. She’s starred alongside some of Hollywood’s biggest names, from Brad Pitt to Ralph Fiennes, Anthony Hopkins, Harrison Ford, and Claire Danes. There is so much more to say about Julia and her career, and I wanted to start there, Julia, because I don’t think we’re going to talk about all of that very much today. We are going to talk about your work combating human rights violations. Why don’t I let you tell us who you are, Julia? So, who is Julia Ormond?

Julia Ormond: I see myself firstly as a mom. I have a kid, and I think much of who I am drops away from that as a priority. I see myself as a human being on planet Earth who is passionate about the notion of our connectivity, how all of our choices and actions are connected. I believe that we can use those to drive an agenda of equality and achieving human rights for people. I’m passionate about equality. And I’m committed to doing what I can to leave the Earth a better place for my kid, and hopefully my kid’s kids.

Zach Coseglia: That’s amazing. I love that. In your founder’s statement on the Asset Campaign’s website, there’s a nice little video, and you reference in that video an aha moment that you had, that drew you to the work that you’ve been doing for the past couple of decades relating to human trafficking and human rights. Tell us about how you got this passion, what that aha moment was.

Julia Ormond: My aha moment that you’re referring to is kind of strange. I’m pretty sure that in that talk, what they were asking for was something a little bit more grounded or something that elevated the work. And for me, I took it in the direction of talking about the fact that I had, when I first encountered the issue of forced labor, child slavery, and was approached by the U.N. to be a goodwill ambassador for it, I was pretty resistant, because I basically saw the issue as predominantly sex trafficking. I then spun that out into, that’s awful, I think it’s horrific, but I don’t have any solutions to offer up for it. I think it’s a government role, and I think it’s a police enforcement role. I was encouraged to go out into the world to look at it, and to pursue looking at solutions. So, I asked the U.N. if I could do that before really representing it, and went on different journeys to look for solutions, to different continents, different areas, starting with Los Angeles. You don’t have to step out of Los Angeles to encounter it.

The aha moment was about the fact that the person who had connected me with it, who I was saying I wasn’t connected to this issue enough, was a woman who was putting me together with people at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. On my first trip, I went to Lake Volta in Ghana. I was working with a nonprofit, Apple, that was an African local nonprofit. As we walked to the lake to see it in situ, they spotted these two young guys coming off the lake, who they said, “We think these are traffickers. We’re going to go and talk with them. Come with us.” I hadn’t prepared myself for what I was going to say or what was going to happen, and it took me a while, because I was looking at the little kid that was holding himself back some distance, carrying these heavy oars, while these two guys were carrying nothing. I turned and looked eventually at the guy that they were talking to, who they felt was a suspected trafficker, and the T-shirt that he was wearing said, “Kennedy Center.” And it just stopped me in my tracks. There was an emotional and even spiritual response that I had to it in terms of it felt like this was very right. I think that that level of commitment, alongside meeting victims, survivors, people who work on the issue globally, and feeling this is so ridiculous that we still have this issue, that we are still doing this to people. There has been something that’s mysterious, that I can’t quantify, but that was deeply personal in that moment to me, that felt like a very direct prod from the universe in terms of how directly connected we are.

Zach Coseglia: You received this really powerful experience. Tell us about what you did with it, how you harnessed that into something more than just a one-time experience, but really into two decades-plus of activism and advocacy.

Julia Ormond: I very much wanted to work on solutions that got to the workforce. Anyone who is enslaved basically shouldn’t be a slave—they should be a member of the workforce. So, I feel that if we had a way to measure slavery in the global workforce, and then also how we’re doing on decent work, and delivering decent work to the global workforce, we could be putting in the positive things that are needed to get somebody to their basic needs, to have their human rights met, from a work perspective in their life. Somebody who has access to all of their rights is the person who is less vulnerable to forced labor or slavery.

Zach Coseglia: Tell us about Asset Campaign.

Julia Ormond: Asset Campaign came about because I very specifically wanted to work on products, products that we’re buying. Those trips around the world would take me to meet people who were trapped in fishing slavery, children in fishing slavery, children in carpet-making, canning pet food, all sorts of things. Every time I would be in that situation of meeting survivors, I would ask the people I was with, “Where does the product end up? Is there a chance this is going into a global supply chain? Could I have been buying this unwittingly?” And they’d always fall silent. So, that then led me to really want to drill into our supply chains to say, “That’s not okay.” We do all sorts of incredibly complicated things as human beings—we actually need to prioritize looking into this and having ways to measure within the supply chain. Asset was … I felt like I needed an organization that focused in on a transparency agenda. Obviously, in that agenda, we joined a lot of people who have a long history of working for corporate accountability, ethics and compliance—the territory and turf that Hui has been groundbreaking on and brilliant on. What we saw in transparency was that there was real opportunity to find something out that would be useful for the consumer, that hopefully could grow, but something that was useful for the consumer in terms of asking companies, “What are you doing?” And that that would then prompt them to actually start doing it, that would bring in resources to measure it. Once we start measuring it, ranking and then racing, if we got to the point where transparency was used for ranking, I actually believe it would be a game-changer for the consumer.

Hui Chen: Julia, this is so fascinating. How do you engage with the corporate community in doing this type of measuring and ranking work?

Julia Ormond: Asset has not felt that we’ve gotten to the sophistication of being able to do that ranking and feeling that it was thorough enough. There are other people who are doing measurement, but what we found was that there are legal hurdles that we have sadly not been able to navigate. I would love to see the transparency agenda ratchet up and go further to reach its promise, because I do think it’s doable, but I think it’s become doable because of AI, because of technology that’s come in. But you will find that it needs to go in a direction of being much more sector-specific. Then, when you get into sector-specifics, you’ll have industries, for instance, like banking, that have the facility to track something, follow the money or see the patterns that would show you that, for instance, there was something going on that was wrong, and break it down into an algorithm. When you have an anomaly within that algorithm, let’s say you have a farmer who has a certain amount of land, he buys a certain amount of seed, you know he needs a certain workforce to generate a crop that he will then sell. At some point, he has to be putting out wages, and those wages need to go into a banking system—if there’s an absence of that, then that should set up a red flag. But we’re nowhere near the depth of detail of that in terms of our response to transparency as legislation. We haven’t gotten to the level where we’ve got consistency, so we haven’t reached and achieved the fairness that I think you need, and also the clarity.

Hui Chen: What do you think are necessary conditions for that to happen, to achieve better consistency and better measurement?

Julia Ormond: The conditions that we need, I thoroughly believe in the transparency agenda, even if it’s not at the moment delivering on its potential—I still believe that it has enormous potential. But you would need a revisit in California. You would need a rallying from the U.N. in order to pull people together, to decide on a strategy, on what is the best strategic path for people to go along. And start with a small step—I think it’s better that you start with something that people can then relate to, implement, measure, and then go onto the next step. I think it takes a decision that affects business globally, and it could be that the only place to do that is actually within the U.N., and business codes of conduct within the U.N. We don’t have yet enough sufficient transparency in how things are done, what the methodology or what the expectations are, and therefore, we don’t have clarity. And so, when you talk with companies, they’re not completely wrong in their frustration and their desire for us to do a better job or have more clarity. What we would want from companies is, I think, a belief in it, that it’s got potential, and to step forward and participate in building out that potential.

Hui Chen: I’m going to take a step back for people who may not be familiar with what corporate transparency in this area looks like. If you can explain to someone who’s new to this area, what do you mean by corporate transparency? What are they supposed to be transparent about? What are the efforts that they’re supposed to be making in order to be transparent?

Julia Ormond: Yes, absolutely. The transparency that we’re talking about is transparency around corporate social impact—specifically, transparency about a company’s program to eradicate trafficking, slavery and forced labor. It started with the Transparency in Supply Chains law in California, which is applicable to large manufacturers and retailers. It asks them what their policy is throughout their supply chain, their direct supply chain to eradicate those. Now, that opens up the idea that you can’t just walk into a supply chain and identify the people who are in forced labor or enslavement—you have to have a policy of the positive, which is delivering human rights. That legislation was then picked up and copied in the U.K. and upgraded. It was built out to be all businesses. They ask for sign-off from the board. And what is regarded as a large company in the U.K. is $36M versus a bar of $100M in the U.S., with a tax footprint in California. So, it’s gone from being a state law that has certain restrictions around it, to a country law. Then, it’s also spreading to due diligence laws in the E.U., it’s gone on to Australia, and each time, it keeps getting more and more robust, more and more meaningful. But I still think we’ve got a battle to keep it relevant, and to be realistic about what it is actually measuring. There are a lot of NGOs. Unseen in the U.K. is fantastic. Verité is a group who does fantastic work in terms of designing, going into the supply chain, looking at what the problems are, what the vulnerabilities are, and specifically designing to make the supply chain more socially impactful. Be Slavery Free is a great organization in Australia that we work with. But I think we’re a long way off where we could be. I don’t mean to be too down on the entire agenda, but I feel that the next round of transparency could get us to the point of measurement, even if it started small.

From the perspective of social impact and environmental, and how those two things go hand-in-hand, for me, it impacts the health of humanity. If as an individual you were sick, let’s say you were a smoker that got cancer. As a human being, you would seek treatment, maybe something laser-specific in terms of the harms. You would need to change your behavior. You would need to tackle an addiction to something. I think I could draw a comparison in terms of the whole of humanity—our workforce has addictive behaviors around forced labor, a reliance on forced labor and too much product, and a resistance to changing that behavior. But we can also laser in—if we were to measure the practices, the social practices and environmental practices throughout the supply chain, the physical supply chain and the value chain, then we’d be able to tackle it holistically from different sides.

Zach Coseglia: On this point about ranking, transparency and the information that you envision or aspire for the consumer to have, what does that look like? Is it literally in an ideal world almost like the nutritional information on the back of a product, that we literally see a profile of how a particular product or particular service is contributing or not to a more socially responsible supply chain?

Julia Ormond: If I book travel, I’ll have a tendency to go to a system that has a star ranking, a five-star ranking, so I would love to see some sort of five-star ranking in terms of, “nothing, one, two, three, four, five.” I think ranking has more potential to encourage people to do more, but you have to do it in such a way that you have to have these standards, and you have to have clarity as to how people are meant to participate. I believe if you had sufficient mass and you had sufficient industries participating, wanting that and driving those standards, then I believe you could set up an agenda where it gets better and better, and the consumer could have more faith in it. But it has to be legitimate, it has to be something that really measures the impact, and, I think, transparency is one tool that allows us to show that we’re all going in a certain direction. Some people ask whether or not the transparency agenda has actually changed how companies behave, and, for me, transparency can’t make claim to that. Transparency is something that tracks progress, either lack of it, or more of it. We can’t actually take claim for the things that companies do—that’s not really how transparency works. So, it’s not the same as the accountability agenda, which I thoroughly believe in. It’s something that supports that agenda, and really, I hope is a transition tool.

Zach Coseglia: It’s interesting, though, because the two really do go hand-in-hand, because once you align on a set of metrics or a set of factors that you want consistently to be transparently disclosed, you’ve also set what the accountability agenda and what folks are going to be held accountable for. I think that in our space, it’s both sides of that coin that are often missing. It’s the lack of transparency, but it’s also the lack of accountability, because there isn’t a consistent standard defining what “good” looks like and what we’re all aiming to achieve.

Julia Ormond: I also think that transparency resonates with people differently. The people who are for the accountability agenda, I think when transparency first came in, felt let down or expressed feeling let down by transparency, because it felt like it maybe kicked accountability further down the road, whereas, I think if transparency is used well, it can bring it forward. I also believe that once we start measuring, there is a different level of incentivization that you can get to. As a consumer, I look at things like fair trade, and I look at corporate response in terms of, “If you want us to do this socially, it’s going to cost more,” and all the rest of it and passing that buck onto the consumer. I think consumers are at the point and past the point of: Why is it that people who care about people and planet are paying more for that privilege, versus the people who are causing the harms, who are able to do that and create a cheaper product as a result of it? As soon as you start measuring people’s relationship to that, you can flip it, and say that people causing harm need to be penalized in some way or need to be paying more than the people who are doing good for people and planet.

Hui Chen: Julia, a couple of episodes ago, we had two business school professors who were on our podcast talking about an analysis they did about whether consumers are willing to pay more for certain aspects of compliance that are directly relevant—their programs—to the products that they were getting. For example, would they pay more for a phone from a company that has a better privacy program? Their answer, at least their finding from the research was, yes, consumers are willing to pay more for certain aspects of compliance that they care about. I do think this is an area where people, they don’t often stop to think about it, but when they stop and think about it, you can get them to care. And when they care, they will be willing to pay more, and do more to facilitate the end goal that we have here. So, a couple of questions that I want to ask you. One is: What would you say to ordinary people who felt like the way you did before you had your aha moment? That this is something that happens in distant lands, or this is something for law enforcement. Human trafficking is bad, but it’s really not something that concerns me so directly. What would you say to them? And two is: What would you say to the people who work in the corporate ethics and compliance space, in terms of what they can do to facilitate their company’s commitment in this area?

Julia Ormond: The first stage of creating a product, I think, very often has the highest frequency, but that is happening because we’re not using our agency at home. I would come back from these trips and be overwhelmed by the lack of transparency and the lack of ability to know whether or not having one of these [holds up mobile phone] had actually killed several people in order to get it into my hands. That’s an unbelievably harsh thing to have to think about, but what I would say is that just by voicing concern, keeping your curiosity there, asking people who are employees—if consumers ask about it, if investors ask about it—then that concern ricochets up to the decisionmakers. But then, you have to also participate and support the laws that are wanting to be more expansive, and to cover more and more. And what I would say to the ethics people is keep working on it—keep arguing for the need for those standards, and for it to go to the next level. Support it in its potential versus have an unfair expectation that it be a silver bullet. It was never a silver bullet. Transparency in California as a law was only ever described as a foot in the door that needed to expand over time, scale over time, and bring with it solutions over time. So, I think keeping up the belief and the faith in it and investing in it and expanding on it is what I would ask of people. Even somebody doing substantive research in terms of these agendas, not just from the point of view of are they working, but from the point of view of: What would make it work? As a mechanism, what does it need to go to the next level? And what would it deliver to the world if everybody was able to make a choice based on what each company was doing, and how each company related to planet and people?

Zach Coseglia: Our Lab very much was built on the idea that multidisciplinary teams are better—that having multidisciplinary teams, where we have people with a diverse background, who have a lot of different experiences, different skill sets, different educational backgrounds, different areas of expertise, just make the problem-solving better. So, I’d love to hear from you a little bit about how your work as an activist and advocate has been made better, or what tools you pull from your work as an actor.

Julia Ormond: I love the diversity angle. I would also say that I actually think strong teams are made of people who have different personality types. You need somebody who’s detail-oriented, who wouldn’t necessarily go to the pub easily with somebody who’s got the 30,000-foot view. But the 30,000-foot view is pretty useless if you don’t have somebody who’s good at implementing it, and that does seem to fall into a personality trait. So, I would look for that as well within a team.

I think in terms of as an actor, there’s a certain thing that comes hand-in-hand with being known to people, that people, right or wrong, have a tendency to be drawn to that, or you can shine attention on something in a different way as an actor, just from the perspective that you’re known. I guess the thing that I have used is curiosity about an individual’s story—people open up to you about what their life experience is, so I’ve been very blessed with that. But it’s a double-edged sword, because, I think, I really underestimated the impact of the trauma of hearing traumatic stories—I wasn’t particularly wise on that front. I think you do have to watch it, especially in a space where people’s experiences, and victims’ and survivors’ experiences can be really quite traumatizing. So, being able to carry that or feel a sense of responsibility for passing that message on, that side of it, I think I’ve had to watch, and I’ve had to make sure that I’m checking in with myself in terms of the impact it’s having on me personally. Hence, there are times when I feel like I need to take a step back, because that can emotionally overwhelm you. And I think when you’re emotionally identifying with something, you’re not necessarily closer to the solution—you are emotionally overwhelmed, versus more insightful. I’ve learned over time to try to find a balance between getting to the heart of the emotional story, trying to process it, and seeing how it fits with solutions. Somebody described it, from the corporate side, as it sometimes feels as if what activists are saying is that water is wet. We identify water because it’s wet, and it’s like, “That’s also oil. That’s also blood. That’s sweat and tears.” There’s lots of things, but from a scientific point of view, it’s H₂O. So, for me, the measurement is critical, because it gets us away from emotional biases and presumptions that on some level, are really useless. But if we were able to measure something and we believed in that measurement, we believed that it was relevant to what was happening, that we were measuring impact, and that people got credit for doing the right thing, even if we were just able to give people credit for funding or investing in the right socially impactful program, then I believe it would take off in a different direction.

Zach Coseglia: That’s actually quite profound. That’s really fascinating. Well done—I like that a lot. Alright, let’s get to know you a little bit better. Everyone who comes on the podcast gets asked a series of questions just so that we and our listeners can get to know them a bit better.

Hui Chen: The first question—you get to choose one of two. You can answer either: If you could wake up tomorrow having gained any one quality or ability, what would that be? Or you can answer: Is there a quality about yourself that you’re currently working to improve? If so, what?

Julia Ormond: I feel I’m currently trying to work on my positivity. People often say, “Are you glass half empty or glass half full?” And I always answer, “It’s both.” It depends on what you want it to be, but in today’s world, I’m trying to work on my positivity.

Zach Coseglia: The next question is also a choice of you can answer one or the other. The first question is: Who is your favorite mentor? Or: Who do you wish you could be mentored by?

Julia Ormond: They’re the same answer. My favorite mentor is my kid. I have looked upwards, or to somebody who’s better at something or feels more experienced at something, but, for me, my kid keeps me grounded, and shares with me their perspective of the world. I really believe that as kids come past us, they are meant to surpass us in our knowledge and our experience, and it should be their vision of the world that we’re serving.

Hui Chen: That’s wonderful. The next question is: What is the best job, paid or unpaid, that you have ever had?

Julia Ormond: Mom.

Zach Coseglia: I had a feeling that’s where you were going to go. That’s great. I think some people were hoping for Legends of The Fall, working with Brad Pitt.

Julia Ormond: I’ll give Legends of The Fall a pretty close second.

Zach Coseglia: The next question is: What’s your favorite thing to do?

Julia Ormond: Walk the dogs with my kid.

Hui Chen: What is your favorite place?

Julia Ormond: I don’t have one.

Zach Coseglia: Alright, we’ll take that. That’s a first—you’re breaking ground, Julia. That’s great. The next question is: What makes you proud?

Julia Ormond: What makes me proud is my kid and being a mom. I’m proud of the fact that I’m 58, and I’ve been a working actor all of my career. And I’m really proud of the accomplishment of the Transparency in Supply Chains law in California. I don’t believe it has reached its potential, but I’m proud of what it did do, and what it seems to have spurred in other areas, by people wanting to top it and do it better.

Hui Chen: Alright, from the profound to the mundane: What email sign-off do you use most frequently?

Julia Ormond: It depends who the person is. If it’s a formal letter of complaint, I drop into very boring, “Yours sincerely.” If it’s a colleague, I try to do, “Best.” And if it’s friends, family or someone I know, I tend to do, “Hugs,” but I have been told that I quite often misspell it, “Jugs,” which is totally inappropriate. So, I do have to double-check that I have actually written “Hugs,” not “Jugs.”

Zach Coseglia: That’s great. The next question is one of our favorites: What trend in your field is most overrated?

Julia Ormond: Confusion that proliferation of something is the same as progress. There have been more and more transparency laws, more and more due diligence laws, but actually, I think without that consistency and that standardization that grows from it, it just becomes more and more complicated, with more and more disclosure requirements, and they actually confuse us being able to measure properly.

Hui Chen: I love that. Last question: What word would you use to describe your day so far?

Julia Ormond: I’m going to say “wonderful.” It’s been wonderful to talk with you.

Zach Coseglia: Julia, it’s been so much fun talking to you today. You’ve been so generous with your time, and with your thoughts and ideas. I know our listeners are going to love this, so thank you so much. And thank you all for tuning in to the Better Way? podcast and exploring all of these Better Ways with us. For more information about this or anything else that’s happening with R&G Insights Lab, please visit our website at www.ropesgray.com/rginsightslab. You can also subscribe to this series wherever you regularly listen to podcasts, including on Apple and Spotify. And, if you have thoughts about what we talked about today, the work the Lab does, or just have ideas for Better Ways we should explore, please don’t hesitate to reach out—we’d love to hear from you. Thanks again for listening.

Stay Up To Date with Ropes & Gray

Ropes & Gray attorneys provide timely analysis on legal developments, court decisions and changes in legislation and regulations.

Stay in the loop with all things Ropes & Gray, and find out more about our people, culture, initiatives and everything that’s happening.

We regularly notify our clients and contacts of significant legal developments, news, webinars and teleconferences that affect their industries.