This article by partners Brenda Coleman, Andrew Howard and Leo Arnaboldi was published by Tax Journal on November 7, 2018.

Setting the scene

The term ‘private equity’ is defined by the British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association as ‘any medium to long term finance provided in return for an equity stake in potentially high growth unquoted companies’. This would therefore encompass venture capital and investment by ‘business angels’ who acquire an equity stake, as well as private equity funds. However, this article will focus on buy-outs by private equity funds, often in secondary deals from other private equity funds.

1. How are tax issues on a private equity deal different from tax issues on other M&A deals?

There are a number of factors that differentiate a private equity deal. Firstly, the importance of leverage. Returns to fund investors on successful investments are multiplied by financing the acquisition using external debt. Deductibility of interest has therefore been of key importance. Historically, deductions have been enhanced by using shareholder debt. New rules impacting deductibility of interest, discussed below, are therefore of particular relevance in modelling returns on private equity deals.

Secondly, there is a focus on exit and distribution of proceeds to investors. Generally, this is within a three to five year time frame. The ability to access double tax treaties to minimise withholding taxes on dividends or non-resident capital gains tax in some jurisdictions therefore becomes particularly relevant.

The next differentiator is the importance of management teams and their expectations as to how they will be rewarded. The tax efficient structuring of management incentives and the avoidance of dry tax charges can be a key component of any bid and can drive the capital structure.

The identity of the ultimate investors in the fund will also differentiate the deal from other M&A deals. Regard will need to be had to tax issues that could impact investors in the fund, particularly US investors and carry holders, in structuring the investment and the optimum life cycle for the investment.

Finally, private equity buyers are competing in a crowded market for the best deals and want to make their bid competitive. Tax is key in driving extra value: care must be taken to minimise irrecoverable VAT and maximise deductibility of expenses. Requests for warranties and indemnities are restricted, particularly from a private equity seller, and insurance may become more relevant. This is discussed below.

Terminology/jargon

2. What is sweet equity?

This is the class of shares typically awarded to management as an incentive. Sweet equity will typically only return value to management (e.g. on a subsequent exit) where the business has performed well under their stewardship, such that other investors have received an agreed level of return.

3. What is a dividend recap?

This is where a company issues new debt (recapitalises) in order to return cash to shareholders by way of dividend or otherwise. It may be used as a means of returning some cash to investors where disposal of the business is undesirable.

4. What is a debt push-down?

A debt push-down is where a business and industrial development corporation (Bidco) looks to ‘push’ acquisition debt down into the target group (sometimes in another jurisdiction) so that the operating companies (Opcos) become the ultimate debtors. This is usually done to ensure maximum efficiency of interest deductibility and flow of funds to service the acquisition debt. Some common techniques include a merger between the Bidco and one or more Opcos, the formation of a fiscal consolidation, and the declaration of a dividend by the Opco which is left outstanding as a debt owed by the Opco rather than settled in cash.

5. What is a management rollover?

It is common in private equity transactions for management to be required to exchange a portion of existing equity in the target for equity in the new structure, thereby reinvesting in the business and helping to align the interests of management with the private equity investor. In such a case, management may be keen to ‘roll’ any gain into the new securities they acquire and thereby defer a capital gains tax charge until a future disposal. As a result, UK management may wish to receive some consideration from the buyer in the form of loan notes (on terms that mean they are non-qualifying corporate bonds’ for CGT purposes), which are then exchanged (or ‘rolled’) up the holding structure using put and call options until securities are finally issued at the desired level.

6. What is a check-the-box election?

Under the US check-the-box regulations, certain listed non-US entities are automatically treated as corporations for US tax purposes, and no election is available to change that status. For example, a UK PLC is a per se corporation for US tax purposes. Any non-US entity that is not a per se corporation, but whose owners have limited liability, is assumed to be a corporation for US tax purposes, unless a check-the-box election is made to treat such non-US entity as a pass-through for US tax purposes. If the non-US entity has only one owner, such entity will be disregarded for US tax purposes as a result of the election. If the non-US entity has more than one owner, a check-the-box election will result in its treatment as a partnership for US tax purposes.

Structure

7. What does a typical UK private equity acquisition structure look like?

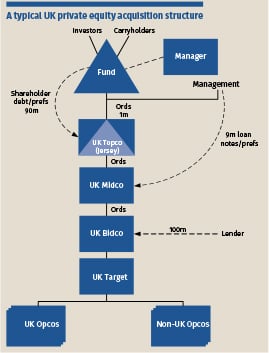

8. What is the purpose of each company?

Starting at the bottom, the Opcos are the operating companies in the target business. UK Target is their existing holding company and the company which is being acquired.

UK Bidco is a newly established UK company, which will draw down the senior finance and make the acquisition. Often, the main board will be at this level and it will provide management services to the Opcos. It may also receive, and pay for, management services from the manager.

Not much activity takes place at UK middle company (Midco) level but it is typically included in the structure at the request of the senior lenders to ease any enforcement of security. In this example, it also issues management loan notes though that is not always the case.

The UK top company (Topco), also a newly established company, is the main equity pooling vehicle into which the private equity fund(s) and rolling management will invest. In this example, it has elected to be treated as a partnership for US federal income tax purposes (see below). It is also the vehicle that is likely to be sold on an exit and can be incorporated in Jersey primarily for the purposes of stamp duty efficiency.

The fund is typically a limited partnership that is expected to be treated as transparent for tax purposes by investors and carryholders. The key decision makers on the acquisition will usually work for the fund’s manager.

While not shown here, some funds are considering making their investments through a ‘Master Luxco’, a Luxembourg company which sits under the fund. Generally speaking, the Master Luxco is expected to qualify for the benefits of Luxembourg’s double tax treaty network. While this isn’t generally necessary in a UK structure from a tax perspective, the risk of a Master Luxco being denied treaty benefits in other jurisdictions is enhanced if it is only used in situations where treaty benefits are actually required.

9. What is the typical capital structure of Topco?

Often, Topco is structured with a comparatively small amount of ordinary shares, with the majority of the fund’s investment being made in the form of loan notes or preference shares. The coupon on these instruments (which typically rolls up) creates a natural hurdle or preferential return for the fund before the sweet equity stands to receive a return. Often, this will allow the sweet equity to be in the form of ordinary shares with the same economic rights as the ordinary shares subscribed by the fund, and thus be ‘memorandum of understanding (MOU) compliant’, allowing management to take the view that it has a very low unrestricted market value for the purposes of calculating the income tax charge on issue where an election is made under ITEPA 2003 s 431 (a ‘s 431 election’).

Alternatively, a similar economic outcome can be achieved by ‘hurdle’ shares – where the hurdle is built into the share rights so that they only have the right to receive distributions/liquidation proceeds once other share classes have been paid up to the specified hurdle. Arguably, however, this is not within the scope of the MOU and makes valuation a more complicated exercise.

10. Preference shares or loan notes?

Traditionally, loan notes have been favoured because of interest deductibility; however, given the new constraints on deductibility (discussed below), preference shares are more common on new transactions. Disadvantages of non-deductible loan notes include the need to manage withholding tax and the need for some recipients, for example, management and UK carryholders, to pay top rates of tax on the interest receipts. Unlike transfer pricing disallowances, there is no provision for corresponding adjustments under the UK’s corporate interest restriction rules. Loan notes are also generally less attractive to US taxable investors in the fund (see question 18 below).

The increased use of preference shares has underlined some uncertainties about their UK tax treatment. Questions include:

- Where exactly does the boundary between fixed rate preference shares and ordinary share capital fall?

- In what circumstances (if any) will the income tax and corporation tax rules on disguised interest apply to treat the dividend or profit on a cum div sale of preference shares as interest?

- Could capital treatment on the redemption or repurchase of preference shares on a dividend recap be susceptible to challenge under the transactions in securities rules?

Preference shares also carry some disadvantages as against loan notes, including being subject to stamp duty on transfer and requiring distributable reserves before payments can be made.

11. Why is substance required in Luxembourg and what does it look like?

Typically, Luxembourg is used as a holding company jurisdiction for investments in many European jurisdictions because, in addition to providing access to a range of service providers, it has a good network of double tax treaties and a competitive tax regime. However, as at September 2018, 84 countries have signed the multilateral instrument (MLI) to modify their bilateral tax treaties regarding entitlement to benefits in line with OECD minimum standards. As a result, it is anticipated that most double tax treaties with Luxembourg will in due course be amended through the MLI to contain (amongst other provisions) a ‘principal purpose test’ (PPT). The exact date of this amendment taking effect for a particular treaty with Luxembourg is uncertain, as Luxembourg is yet to confirm ratification of the MLI to the OECD. However, the amendment to Luxembourg treaties could take effect for non-resident capital gains taxes as early as 2019 Q2 (with withholding taxes following from January 2020).

The OECD has released three examples of how various jurisdictions might choose to interpret the PPT in the treaty in relation to collective investment vehicles. The examples are not necessarily consistent but one suggests that the PPT may be satisfied where the fund invests through a ‘regional investment platform’ where investment, treasury, regulatory and administrative functions are performed. Although this example is provided in the context of a single institutional investor, some private equity funds are considering the use of a master holdco and also, as far as possible, moving these functions to Luxembourg (or other platform) in order to provide ‘substance’.

Further, even prior to the introduction of the PPT, tax authorities in some jurisdictions, for example Germany, Spain and Italy, were requiring detailed information on ‘substance’ in Luxembourg (or other holding company jurisdiction) before access to their treaties is permitted. Questions on substance have been focused around the residence/expertise of directors, the availability of dedicated office space and employee numbers and functions.

Some further indication of what substance may look like for the purposes of the PPT may be taken by analogy from the recent consultations launched in Jersey and Guernsey concerning the inclusion of a substance requirement in their tax laws.

Financing

12. What impact has the corporate interest restriction had on private equity deals?

The introduction of the corporate interest restriction in TIOPA 2010 Part 10 has had a material adverse impact on the efficiency of traditional UK private equity structures. A simplified numerical example of the impact of the new rules on the structure in the diagram (previous page) is to assume that UK Bidco pays 5% interest on its loan, and that Topco and Midco pay 10% interest on the shareholder debt (half of which is accepted as being on arm’s length terms). This provides a shield from tax on £10m of UK profits annually. Following the introduction of the rules discussed below, that shield may drop to as little as £2m, an increase in the annual tax bill of more than £1.5m.

As readers will be aware, from 1 April 2017 restrictions apply for groups with net annual interest deductions in the UK in excess of £2m. The basic rule is that deductions for interest above that amount will be restricted to the extent that they exceed 30% of the group’s UK EBITDA as calculated for UK tax purposes. If the worldwide group has a level of interest expense on external leverage which exceeds 30% of the group’s EBITDA, this threshold may be raised to that level (the ‘group ratio test’) by election.

For many structures, these rules are likely to mean that any shareholder debt is no longer deductible. It is sometimes assumed that the group ratio test will preserve the deductibility of third party debt. However, such deductions may also be restricted, particularly where UK debt is used to fund the acquisition of groups with some operations outside the UK. In the example in diagram, all the group’s external debt is in the UK, but half of the group’s EBITDA is attributable to its non-UK operations. As a result, the group ratio test will not assist (on the numbers) and the 30% cap will apply.

In response to the corporate interest restriction rules, and bearing in mind that many other jurisdictions have similar restrictions, it is becoming common to see acquisitions accompanied by reorganisations which allow debt to be better aligned with profits in the jurisdictions where the group has business activities. Some techniques are discussed in question 4.

Another impact of the demise of shareholder debt is that other forms of tax shield, such as carry forward losses and deductions relating to incentives, have become more valuable as they are more likely to result in a cash tax saving. For the same reason, the tax value of deeply subordinated finance, provided by third parties rather than shareholders, has increased.

Finally, it should be noted that there are still situations in which carefully structured shareholder debt can be deductible, particularly where acquisitions are not leveraged by third party debt.

13. Do the hybrid rules need to be considered?

Should any shareholder debt have survived the corporate interest restriction, it is also necessary to consider the hybrid mismatch rules in TIOPA 2010 Part 6A. These rules seem most likely to impact private equity funds with a material contingent of US investors. In the structure in the diagram (page 11), a check-the-box election has been made for UK Topco. Since UK Topco has multiple owners consisting of the fund and members of management, it is a partnership for US tax purposes. Under an alternative structure, if the fund were the only owner, and if management held its ordinary equity at a lower level, UK Topco would be a disregarded entity (DRE) for US tax purposes. Such DRE status might be advantageous if the fund wanted to engage in transactions with UK Topco for purposes of non-US law but wished to have those transactions disregarded for purposes of US tax law. For example, if the fund made an interest-bearing loan to UK Topco while it had DRE status for US tax purposes, the loan would be respected for UK and Jersey purposes; but for purposes of US tax law, the fund would be treated as having made a loan to itself, and consequently US tax law would disregard the loan and any interest paid or accrued thereunder.

However, making the election means that UK Topco will be treated as a hybrid entity and it is therefore necessary to consider whether there is a ‘deduction/non-inclusion mismatch’ for the shareholder debt. As the effect of the election is that the income from the shareholder debt is not taxed as ordinary income for US tax purposes, such a mismatch is likely to be taken to arise for US investors (including tax exempt US entities due to the ‘relevant assumptions’ required under the rules). Deductions (including but not limited to interest deductions) will be denied (or at least postponed) to the extent of the mismatch.

The situation could be rescued if there were any ‘dual inclusion income’, taxable in both the UK and the US, to offset the deductions. However, the UK rules and HMRC guidance take a restrictive view of the circumstances in which such income will arise; and in any case, where, as here, the UK deductions will be surrendered by way of group relief into an unchecked operating subsidiary, such a rescue would not seem consistent with the purposes of the legislation.

Third part debt is unlikely to be affected. Concerns that debt fund structures could lead to interest paid by arm’s length borrowers to debt funds being non-deductible have largely been put to bed by amendments to the legislation and HMRC guidance.

Management

14. How is management in portfolio companies typically incentivised?

The size and ownership structure of private equity-backed companies typically means that UK management are unable to benefit from statutory tax-advantaged incentive arrangements, such as EMI options. However, as noted in the response to question 9, the capital structure is typically geared in such a way that a manager’s ‘sweet equity’ investment in the company’s ordinary shares should provide a tax-efficient incentive to generate equity value growth.

Returns on the disposal of such ‘sweet equity’ shares can be expected to qualify for CGT (at significantly lower rates than income tax). In addition certain key managers may be able to qualify for entrepreneurs’ relief, though this is expected to be less common following the recent Budget changes: as well as extending the period of time for which a relevant shareholding must be held from 12 months to 24 months, the shares must now also beneficially entitle the holder to at least 5% of the profits available for distribution to the equity holders of the company and, on a winding up of the company, to at least 5% of the assets of the company available for distribution to equity holders.

One disappointing aspect is that the changes do not grandfather existing arrangements. Managers who have recently rolled over a holding of shares in respect of which the entrepreneurs’ relief qualification criteria were met into a new shareholding which will not now qualify should therefore consider whether to elect to trigger a disposal on that exchange of shares or loan notes in order to claim entrepreneur’s relief.

15. A new manager is joining: can new shares be issued?

Given the lifespan of private equity investments, it is common for new senior managers to be appointed during the life of an investment. Where that happens, clients often ask whether the existing sweet equity pot can be used to incentivise the incoming employees. From a UK tax perspective, the key question typically concerns the valuation of this equity award. Unless a UK manager pays unrestricted market value for the award (assuming, as is typical, a s 431 election is made), the award of shares is likely to trigger a general earnings charge under ITEPA 2003 s 62.

HMRC has shown itself to be increasingly sceptical of low-or-zero valuations being adopted for equity granted to managers in highly geared private equity scenarios. Unlike US ‘profits interests’, it is unlikely to be sufficient to justify a low valuation by relying on the equity being underwater on a simple liquidation basis where an ‘expected returns’ or ‘option pricing’ methodology would show a different result. Companies in this situation should consider engaging expert valuations advice before awarding equity to incoming managers.

Higher valuations mean that we are likely to see an increasing number of situations where equity prices mid-investment have risen to a level where it is unattractive for new managers to acquire these shares at their market value. There are two obvious solutions for companies in this situation that are still determined to grant equity awards. Either some form of financial support (e.g. in the form of a loan or bonus) could be provided to assist in acquiring the equity; or more fundamental changes may need to be made to the equity package to reduce the value of the relevant shares (e.g. introducing a further value hurdle that must be satisfied before the shares participate).

16. Can a loan be made to managers to buy the shares?

This is generally possible. However, the tax implications of loans to management can be complex. In addition to navigating the normal employment tax and disguised remuneration concerns that come with making loans to employees, it is worth noting that most UK companies that are owned by private equity funds are likely to be ‘close’ for UK tax purposes. As a result, the portfolio company will need to consider whether loans to individuals could trigger liabilities under the loans to participators provisions of CTA 2010 Part 10. Furthermore, since April 2018, it has also been important to consider whether the close company gateway under the disguised remuneration rules could be engaged. In short, there is a range of highly technical provisions that can trap the unwary and which could trigger liabilities or risks that would be exposed in diligence at the time of an exit if timely advice is not taken.

17. Is an EBT required?

Employee benefit trusts (EBTs) are offshore trusts set up for the benefit of employees as a whole. They are often used as a warehousing vehicle for management shares. Shares may be issued directly to the EBT at the time of the acquisition for distribution to management at a later date. Alternatively, EBTs may acquire shares from leavers to ensure that the value attributable to the leaver shares is retained for the benefit of other employees.

The cost and complexity that can be created through using an EBT can be underestimated. It is sometimes worth considering other warehousing mechanisms, such as holding shares in treasury, on a case by case basis. From a tax perspective, there are many issues to consider with EBTs, not least inheritance tax. It is worth noting that EBTs do not solve the issues discussed in question 15; shares acquired from an EBT will be treated in the same way as newly issued shares.

US investor issues

18. What issues are important to US investors in the fund?

Many private equity funds have US investors that are tax-exempt in the US. Typically, these investors are pension funds and tax-exempt institutions such as universities. These US tax-exempt investors will want to avoid unrelated business taxable income (UBTI), because an otherwise tax-exempt investor would be required to pay US tax on its UBTI.

A US tax-exempt investor can have the misfortune of recognising UBTI in two ways. First, the US tax-exempt investor will recognise UBTI if there is no entity that is a corporation for US tax purposes between the investor and the operation of the business. For example, in order to avoid UBTI in the structure in the diagram (page 11), UK Topco, which has elected to be treated as a partnership for US tax purposes, should be a pure holding company and should not conduct any aspect of the operating business. UK Midco or any entity below UK Midco could conduct the operating business. As a result, US private equity funds with US tax-exempt investors will typically restrict any check-the-box elections that they make to non-US entities that are pure holding companies and do not have any business operations.

Second, a US tax-exempt investor will also have UBTI if it has ‘unrelated debt-financed income’ (UDFI). A US tax-exempt investor will have UDFI if it recognises capital gains or dividend income with respect to an investment, and if within 12 months of that recognition there was debt in the capital structure between the investor and the first entity in the structure that is a corporation for US tax purposes.

In the structure depicted in the diagram, the shareholder debt between the fund and UK Topco is potentially problematic. From the standpoint of a US tax-exempt investor, preference shares would be preferable to shareholder debt. Alternatively, the shareholder debt could be retired at least 12 months prior to the recognition of any income with respect to the investment. In general, the amount of any recognised income that is UDFI will be in proportion to the amount that the offending debt represents of the total capital structure. The £100m of debt incurred by UK Bidco does not raise any UDFI concerns, because UK Bidco is a corporation for US tax purposes.

Taxable US investors do not have UBTI concerns, but they will want to avoid the receipt of ‘phantom income’ (taxable income that does not come with cash). Phantom income can result if certain US investors each own more than 10% of the stock of a non-US corporation and if those 10% US stockholders collectively own more than 50% of the stock of such non-US corporation. Such a non-US corporation is a controlled foreign corporation (CFC), and certain income of a CFC is taxed immediately to its 10% US stockholders, even if such income is not repatriated to such 10% US stockholders.

If a US private equity fund organised as a limited partnership in Delaware acquires all of the stock of a non-US corporation, the non-US corporation will be a CFC, because the US tax law treats the US private equity fund as a single US stockholder that owns 100% of the non-US corporation. In order to avoid CFC status for such a non-US corporation, many US private equity funds will avail themselves of alternative investment vehicle (AIV) provisions in their organisational documents.

Such an AIV provision will enable a US private equity fund to establish an AIV as a non-US partnership, often in the Cayman Islands. The limited partners of the US private equity fund will invest directly in the AIV, and the AIV will acquire the non-US corporation. For the purposes of determining whether the non-US corporation is a CFC, the AIV will not be a US stockholder because it is a non-US partnership. Instead, the US tax law will look through the AIV to determine whether any of the investors in the AIV are US persons that have an indirect 10% or greater interest in the non-US corporation. If there is sufficient dispersal in the ownership of the US private equity fund, there will be no 10% US stockholders in the non-US corporation.

Many US private equity funds have always sought to avoid CFC status for their non-US portfolio companies due to the immediate taxation in the US of generally passive investment income such as capital gains, dividends and interest recognised by CFCs as ‘Subpart F income’. Following US tax reform, however, avoiding CFC status has taken on added importance due to the new global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) rules.

Very generally, under the GILTI rules, the 10% US stockholders of a CFC pay immediate US tax on the operating income of a CFC that exceeds a 10% annual return on the tax basis of the CFC’s tangible assets. The GILTI rules do not apply to operating income that is taxed by a non-US jurisdiction at a rate at least equal to 90% of the US 21% corporate rate, or 18.9%.

Transaction issues

19. Why is the tax indemnity capped at a pound?

Contractual tax protections on private equity transactions tend to be different from those found on other M&A deals. Where a private equity house is selling, it is likely to be very focused on not having a tail of liability, such as contingent liability under a traditional tax deed. This is because the seller will be keen to return proceeds to investors, rather than having to retain some of the proceeds to protect against contingent tax deed claims. For this reason, it is common to find a combination of contractual protection given by management sellers only, very low caps and very tight time limits. As a result, buyers who have identified issues they are uncomfortable with in the course of their diligence will often look to insurers, who are often prepared to offer more comprehensive cover (for a fee, which is sometimes split). The typical way of receiving insurance coverage is to include the desired protection (e.g. tax deed and warranties) in the sale documents but to limit the sellers’ liability at one pound. The insurers will then agree to underwrite any additional loss (subject to agreed limits) in a contract of insurance. The tax issues relating to warranty and indemnity insurance have been the subject of several recent articles in this journal (for instance, see ‘Tax indemnities: lessons from recent litigation’ (Richard Jeens & Charles Osborne) Tax Journal,3 May 2018, and ‘The taxation of pay-outs under buy-side warranty and indemnity insurance policies’ (Gareth Miles) Tax Journal, 1 December 2016).

20. What should I look for in the funds flow?

The funds flow is the Excel model which will be prepared by the clients’ financial advisers to track the price and the various payments that will need to be made at closing. As with any deal, in order to allocate tax risk properly, it is crucial to understand how the deal pricing mechanics work. On private equity transactions, this can become extremely complicated as there are often a large number of sellers, as well as significant sums flowing through the target on or around closing. Tax issues which frequently arise include:

- the correct application of employment taxes (particularly employer’s NICs);

- the correct application of VAT; and

- what level of tax deductibility is expected for fees and other payments.

Once a picture of the likely level of cost and benefit has emerged, it is necessary to consider how these should be allocated between buyer and seller. Even more confusingly, these issues may or may not be taken into account before arriving at the headline price under the sale and purchase agreement (in the ‘bridge’). It is necessary to work closely with the client’s financial advisers to make sure that these issues are being appropriately addressed both in the funds flow and in the sale documents.

Authors

Stay Up To Date with Ropes & Gray

Ropes & Gray attorneys provide timely analysis on legal developments, court decisions and changes in legislation and regulations.

Stay in the loop with all things Ropes & Gray, and find out more about our people, culture, initiatives and everything that’s happening.

We regularly notify our clients and contacts of significant legal developments, news, webinars and teleconferences that affect their industries.