Authored by Vincenzo Volpe and Catherine Morey.

Just over one year ago, the COVID-19 pandemic hit the pharmaceutical industry with unprecedented challenges and opportunities. On the one hand, it allowed the industry to demonstrate its value on a global scale through the development of vaccine programs. On the other, it led to short and long-term hurdles, particularly as regards supply shortages, research and development shifts (and resultant approval delays), and new ethical dilemmas.

The political and enforcement headwinds that came with these challenges add another layer of complexity. Competition and other regulatory authorities around the world are increasingly interventionist in their approach to behaviours and mergers in the pharmaceutical sector. As legislative reforms progress and develop, pharmaceutical firms must continue to consider their engagement strategy with authorities to help shape the reforms, and to minimise the uncertainty associated with regulatory scrutiny.

We set out four trends in pharma deal-making in 2021, and the key regulatory considerations associated with them.

1. Enhanced merger control scrutiny

Prior to the pandemic, pharma M&A was soaring, with deals totalling $414 billion in 2019, an all-time high (per McKinsey & Company). The global health crisis and the uncertainty associated with the U.S. presidential election (and its potential impact on drug policy) caused a lull in pharma M&A activity in the first half of 2020, but it was short-lived. As negotiations and deal-making pick up again, biopharmaceutical and health care companies might consider how the following may affect deal timeline and implementation.

a) The Multilateral Working Group to Build a New Approach to Pharmaceutical Mergers

Pharmaceutical mergers remain an enforcement priority among competition authorities globally, particularly as the health crisis brings questions about drug pricing and market access conditions into sharp focus. On March 16, 2021, acting FTC Chairperson Rebecca Slaughter announced the formation of an international working group that will seek “to identify concrete and actionable steps to review and update the analysis of pharmaceutical mergers”.1 Initiated by the FTC, the working group will include the Canadian Competition Bureau, the European Commission (EC), the U.K.’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), and Offices of State Attorneys General.

Commissioner Slaughter noted that the group “intend[s] to take an aggressive approach to tackling anticompetitive pharmaceutical mergers”, particularly in light of “the high volume of pharmaceutical mergers in recent years, amid skyrocketing drug prices”. The working group will share expertise and discuss questions relating to:

- The theories of harm that enforcement agencies should consider when evaluating pharmaceutical mergers;

- The effects of a pharmaceutical merger on innovation, and the challenges that arise when mergers involve proprietary drug discovery and manufacturing platforms;

- How the risks or effects of conduct such as price-setting practices, reverse payments, and other ways in which pharmaceutical companies respond to or rely on regulatory processes, should be considered;

- How to approach market definition, particularly in the context of new or evolving theories of harm;

- The evidence that may be relevant or necessary to assess, and if applicable, challenge a pharmaceutical merger based on any new or expanded theories of harm, and the types of remedies that would work;

- What types of remedies would work in the cases to which those theories are applied; and

- The factors, such as the scope of assets and characteristics of divestiture buyers, that influence the likelihood and success of pharmaceutical divestitures to resolve competitive concerns.

The working group issued a notice seeking public comments on the above issues on May 11.

b) The European Commission’s new Article 22 Guidance on case referrals

The EC has also taken steps to assert jurisdiction over transactions targeting low revenue generating/pre-commercial, yet disruptive, entrants.

Back in September 2020, Commissioner Vestager announced that the EC planned “to start accepting referrals from national competition authorities of mergers that are worth reviewing at the EU level, whether or not those authorities have the power to review the case themselves”.2 Only six months later, the EC issued Guidance on referrals under Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation.3

Article 22 already permitted referrals from Member States lacking jurisdiction to review a transaction under their national merger control rules. However, the EC has had a long-standing practice of discouraging referrals, recognizing that “such transactions were not generally likely to have a significant impact on the internal market”.4 The new guidance reverses the EC’s policy by indicating that Article 22 is applicable to all concentrations, not only those that meet the jurisdictional criteria of the referring Member State(s). This change is a significant development for dealmakers and legal advisers: any transaction that may be perceived as raising competition concerns could end up being reviewed by the EC (no matter how small the target), even after the deal has closed. While the Guidance states that “the EC would generally not consider a referral appropriate where more than six months has passed after the implementation of the concentration”,5 the six month-period only starts from when the EC learns “material facts” about the deal.

As referrals may affect the timing and feasibility of transactions, parties to a concentration falling below national thresholds will systematically need to assess whether their deal can affect competition in any EU Member State. Parties will also have to balance the risks involved with closing quickly and challenging a possible post-closing referral, or seeking reassurance from the EC and relevant National Competition Authorities (NCAs) that they will not refer.

The Guidance applies to all transactions, but primarily targets deals in the digital economy and pharmaceutical/life sciences sectors. Transactions more likely to attract scrutiny are those where:

- One party is a start-up or recent entrant with significant competitive potential that has yet to develop or implement a business model generating significant revenues (or is still in the initial phase of implementing such business model);

- One party is an important innovator or is conducting potentially important research;

- One party is an actual or potential important competitive force;

- One party has access to competitively significant assets (such as, for instance, raw materials, infrastructure, data or intellectual property rights); and/or

- One party provides products or services that are key inputs/components for other industries.

NCAs in France and the Netherlands have already relied on the new Guidance and referred Illumina/Grail, a deal in the genomic cancer testing space, to the EC. The EC has accepted the referral request – despite the fact that the transaction did not trigger merger control filings in any EU Member State – and has since announced that authorities in Belgium, Greece, Iceland and Norway have joined the referral. Illumina and Grail challenged the move in national courts, but were unsuccessful. An appeal to the European General Court is pending.

c) Expansion of national merger control thresholds

Since its decision in Roche/Spark, the UK CMA has continued to rely on a broad application of the share of supply test to ensure certain deals fall within its remit. The authority is determined to review non-UK acquisitions even where targets are only tangentially connected to the UK. In March 2021, the CMA updated its merger assessment guidelines to capture an evolved approach to reviewing mergers and reflect the evolution in markets and the economy over the past decade. A key area of focus in the revised guidelines is the importance of non-price aspects of competition, such as innovation.

Other NCAs such as Austria and Germany introduced transaction value thresholds in [2016]. These already aimed to enable inter alia jurisdiction over high premium acquisitions of pre-commercial assets by large pharmaceutical companies. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that, at least for now, Austria and Germany have not been supporting a referral under the EC’s new Article 22 Guidance.

d) Adoption of SPAC structures

There is an increasing trend among biotech companies to go public through a merger with a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC). Examples include Cerevel Therapeutics/Arya Sciences Acquisition Corp II, Nuvation Bio/Panacea Acquisition, and Celularity/GX Acquisition. The advantages associated with SPAC structures are the faster timeline compared to an IPO process, and greater valuation certainty as a target can lock in a negotiated price before the announcement of the transaction.

Merger control issues may arise as the same sponsors acquire larger interests across targets active in the same therapeutic field.

2. EC comfort letters and R&D collaborations

The COVID-19 outbreak caused a severe disruption of supply chains, combined with a steep rise in demand for products and services related to the health sector. These exceptional circumstances created a short-term need for pharmaceutical and other health care companies to cooperate (particularly in the field of generics) in order to overcome, or at least to mitigate, the effects of the crisis to the ultimate benefit of citizens.

In April 2020, the EC published a Temporary Framework Communication6 to provide antitrust guidance to companies cooperating in response to urgent situations related to COVID-19. The EC also issued a “comfort letter”7 concerning a specific cooperation project aimed at avoiding situations of shortages of critical hospital medicines. The letter emphasizes that discussion of prices or unnecessary coordination remains unlawful, and warns companies not to raise their prices beyond what is justified by possible increases in costs.

In March 2021, the EC issued a second comfort letter in respect of a “Matchmaking Event” organised so that manufacturers of raw materials and companies with production capacity can engage on a confidential basis with the developers and manufacturers of COVID-19 vaccines to address issues of scarce supply. The Commission has confirmed that the event does not raise concerns only insofar as information exchanges are “limited to what is indispensable for effectively resolving the supply challenges linked to COVID-19 pandemic”.8 Importantly, direct competitors cannot share “any confidential business information regarding their competing products, in particular information relating to prices, discounts, costs, sales, commercial strategies, expansion plans and investments, customer's list, etc.” If direct competitors believe sharing that kind of information will be indispensable to finding a solution for scaling up vaccine supply, they are told to contact the Commission for specific guidance.

Although interim authorisations and comfort letters provide a degree of certainty, they do not protect companies from investigations. The EC will continue to use its investigative powers (including dawn raids) to uncover and prosecute cartel infringements.

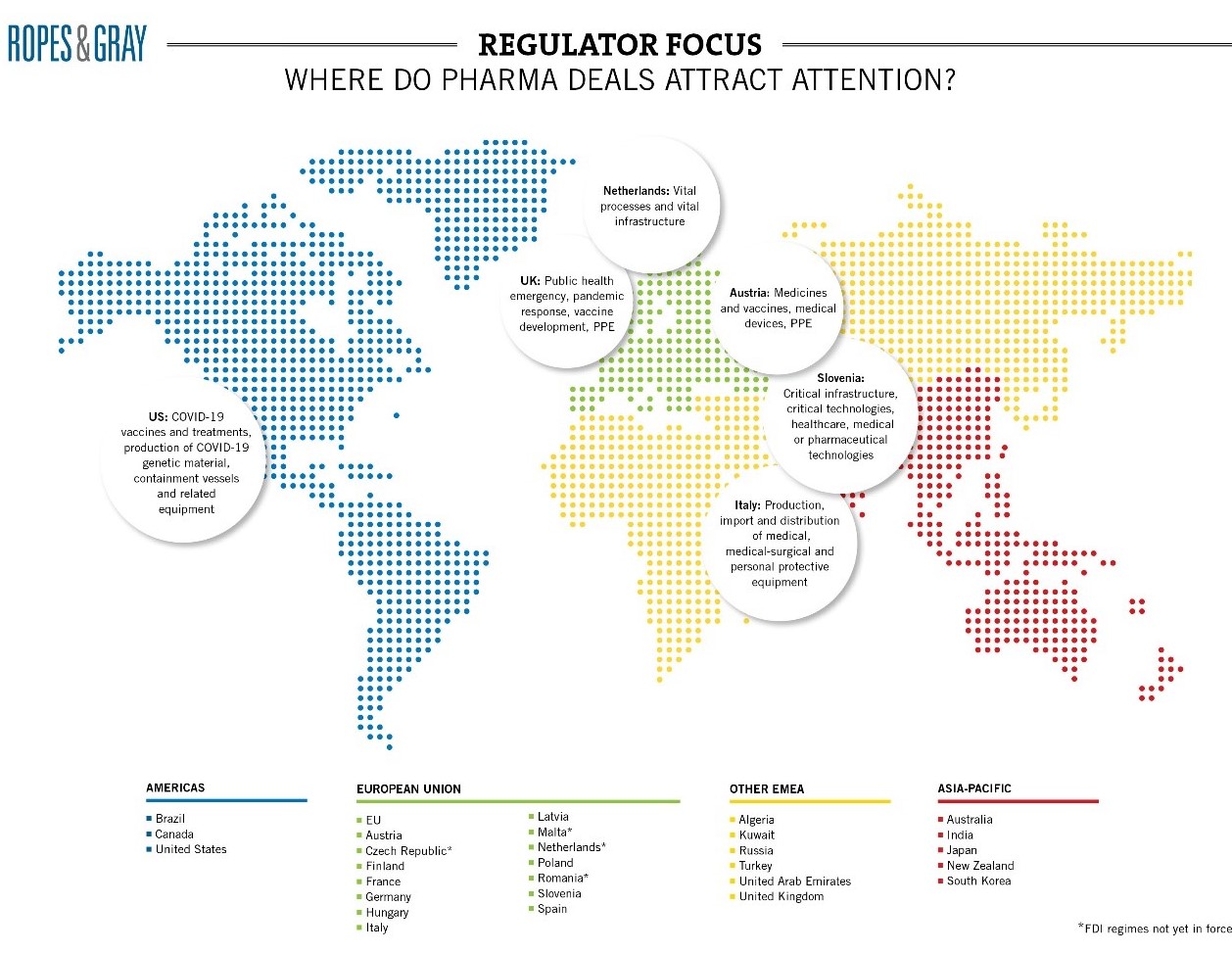

3. Foreign Direct Investment ― Global scrutiny

Last, but certainly not least, is the global rise of foreign investment restrictions. Accelerated by COVID-19 and potentially the U.S. CFIUS experience, pharma, biotech and other healthcare operations feature prominently on most FDI watch lists and are likely to remain in focus even as we (hopefully) move into the recovery period.

In Europe, Member States have introduced a host of new measures over the past 12 months to implement the EU’s FDI Screening Regulation, which captures investments in a range of critical infrastructure, critical technology, critical inputs, and sensitive data. Member States may share information with each other and with the EC about FDI notifications and investigations in their jurisdiction, which will make the EU a more strenuous environment for foreign investors in the years ahead. FDI restrictions are also tightening in the UK, where a new mandatory and suspensory (and retrospective) regime should be introduced at the end of the year with secondary legislation (due in July) expected to further define sectors.

Other jurisdictions expected to introduce regimes in 2021 include Hungary, Denmark, Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands. The Czech Republic’s regime recently came into force on May 1. Some regimes have already seen multiple amendments, with Germany counting 17 in relation to the Außenwirtschaftsverordnung, “AWV”. The AWV now captures medicinal products and their starting materials or active substances (insofar as they are essential for health care according to the German Medicinal Products Act), medical devices for life-threatening and highly contagious infectious diseases as well as diagnostic agents for infectious diseases (cf. section 55 para. 1 sentence 2 numbers 9, 10 and 11 AWV new). Such wide definitions mean that very few pharma transactions will remain wholly outside the scope of the regime.

The fast-moving FDI landscape can make potential issues hard to spot in diligence. Concerns can arise in relation to minor parts of the target’s business, such as small government contracts. This uncertainty should be carefully weighed in risk allocation mechanics and long-stop dates because standstill obligations and sanctions for gun-jumping mean that transactions cannot close while agencies are investigating.

What’s next?

The pharmaceutical industry is under the spotlight, and that is not likely to change anytime soon. An increasing number of regulators are closely monitoring the sector and developing new tools to review (and potentially oppose) mergers and behaviours perceived as even remotely anti-competitive.

In order to minimise antitrust risk (including severe administrative and criminal sanctions), and disruption on deal timelines, early antitrust diligence is essential. As pharmaceutical companies navigate these stormy seas, contractual protection relating to antitrust is increasingly requiring a premium and may occupy centre stage in deal negotiations.

- See FTC announcement for additional information, available at https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2021/03/ftc-announces-multilateral-working-group-build-new-approach.

- See International Bar Association 24th Annual Competition Conference, available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2019-2024/vestager/announcements/future-eu-merger-control_en.

- The guidance is available at https://ec.europa.eu/competition/consultations/2021_merger_control/guidance_article_22_referrals.pdf.

- Article 22 Referral Guidance, paragraph 8.

- Article 22 Referral Guidance, paragraph 21.

- Available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/framework_communication_antitrust_issues_related_to_cooperation_between_competitors_in_covid-19.pdf.

- Available at https://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/medicines_for_europe_comfort_letter.pdf.

- See https://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/comfort_letter_coronavirus_matchmaking_event_25032021.pdf.

Authors

Stay Up To Date with Ropes & Gray

Ropes & Gray attorneys provide timely analysis on legal developments, court decisions and changes in legislation and regulations.

Stay in the loop with all things Ropes & Gray, and find out more about our people, culture, initiatives and everything that’s happening.

We regularly notify our clients and contacts of significant legal developments, news, webinars and teleconferences that affect their industries.